Religion and art have enoyed a centuries-old relationship. Creations inspired by the divine don’t just tell a story, glorify, mythologize, or idealise their subject matter. They are capable of inspiring and creating a sense of awe and wonder in the most unreligious soul.

Christianity in particular has had a profound impact on Western art. To this day, nearly a third of paintings in The National Gallery’s collection of Western European art are of religious content, and nearly all of them are inspired by the Christian faith.

The mysteries of the afterlife, the nature of soul-body duality, the suffering of Christ, the glory of God, the concept of sin, and the question of eternity are just a few of the themes that Christian art through the centuries has captured in broad strokes and devilish detail.

The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes, The Annunciation by Nicolas Poussin, Christ Contemplated by the Christian Soul by Diego Velázquez, The Entombment (or Christ being carried to his Tomb) by Michelangelo, and The Virgin of the Rocks by Leonardo da Vinci are just a handful of masterpieces that have made the viewer step outside of themselves for a few heartbeats with the sense of something elusive and fleeting fluttering on the edge of their waking mind.

Since time began, humanity has been striving to capture that which it regards as divine, holy, and sacred in its artistic creations.

In some cases, these creations have seemingly captured the sense of otherness and mysticism so adeptly that they can have an almost transcendental effect on those who view them.

In 1817, the French author Henri-Marie Beyle, better known by his pen name Stendhal. visited the largest Franciscan church in the world, the Basilica of Santa Groce in Florence for the first time to view Giotto’ renowned ceiling frescoes.

Niccolò Machiavelli, Michelangelo, and Galileo Galilei are all buried at the Florence Cathedral, and so it carries a lot of historic weight, but on the occasion, it was the famous frescoes by Giotto that Stendhal had come to see.

The 14th-century Florentine artist is widely regarded as the father of Italian painting and the frescoes, which tell the stories of the life of Saint Francis, are one of his most iconic works. So you can imagine they pack a pretty mean punch.

However, for Stendhal, they proved life-changing.

In his book, ‘Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio’ Stendhal recalls he wasn’t just transfixed by the art he was transformed.

He remembers looking at the frescoes and writes, “I was in a sort of ecstasy, from the idea of being in Florence, close to the great men whose tombs I had seen. Absorbed in the contemplation of sublime beauty I reached the point where one encounters celestial sensations. Everything spoke so vividly to my soul. Ah, if I could only forget. I had palpitations of the heart, what in Berlin they call ‘nerves.’ Life was drained from me. I walked with the fear of falling.”

In other words, Stendhal was having what today we’d call a panic attack and was close to passing out.

Overwhelmed by his reaction to the religious artwork he was forced to flee the cathedral and seek refuge on a bench outside, where he recited poetry to calm his nerves and steady the vision.

Some critics would later suggest that Stendhal was under the influence of the ‘Green Fairy’ or absinthe as it's more commonly known.

Yet the absinthe craze amongst French artists and writers wouldn’t take hold for another century or so.

Stendhal’s extreme reaction to religious art was eventually recorded by posterity as the ’Stendhal Syndrome.’

First coined in 1979 by the head of psychiatry at Florence’s Santa Maria Nuova hospital, Graziella Magherini, the fainting in the face of paintings, also known as an ‘art attack,’ had apparently become a real thing in Florence, blessed as it was with a wealth of religious art.

Between 1977 and 1986, Doctor Magherini and her team diagnosed 107 cases of “acute and unexpected psychiatric breakdown among tourists exposed to artworks.’

In a 2019 interview with students from the European Humanities University, Magherini points out, “The episodes were the product of not one fact but many. Including sensitivity, the structure of your personality, traveling itself which deprives you of your daily points of reference, and finally, the encounter with the great masterpieces.”

Often described as Florence Syndrome, because that great city of religious art is where a lot of cases occur, novelists Marcel Proust and Fyodor Dostoevsky were also thought to suffer from the condition.

When looking at the Dead Christ painting by Hans Holbein on a trip to the Basel Museum, Dostoevsky was said to stand ashen-faced and still for 20 minutes in front of the artwork which depicts Christ taken down from the cross.

He was so disorientated and agitated by what he was seeing his wife had to take him by the arm and walk him away.

As Einstein once said, “Art is standing with one hand extended into the universe and one hand extended into the world and letting ourselves be a conduit for passing energy.”

To this day art and religion enjoy a close alliance and it’s something that will be celebrated in a curated art trail in remote rural churches near the Black Mountains between Usk and Hay-on-Wye beginning in early August and running to late October.

They are hoping people don't faint!

Organised by Art and Christianity and Friends of Friendless Churches, and curated by Jacquiline Creswell, each church will host a different artwork selected to augment the site and to convey the richness of the theme of ‘vessels’.

Jacquiline explained, “Vessel is a curated art trail in remote rural churches near the Black Mountains between Usk and Hay-on-Wye. Seven artworks by seven artists will be shown in seven churches, six of which are maintained by the Friends of Friendless Churches who keep them open all year round. The theme of ‘vessel’ references bodies, boats, secretions, and receptacles; each of the artworks will be sited in a particular relationship to the church and its materials.

“The exhibition will be open from early August 2024 to late October, ensuring the optimum season for visitors to the churches. It will create a memorable and unique placement of art within a conjunction of landscape and architecture that is often overlooked. It will bring artists of international reputation to an area of outstanding natural beauty.

“It is the first time an exhibition like this trail has taken place in these churches.”

The artists participating are Lou Baker, Barbara Beyer, Andrew Bick, Robert George, Lucy Glendinning, Jane Sheppard, and Steinunn Thórarinsdóttir. And the venues include St Michael and All Angels', Gwernesney, St Cadoc, Llangattock Vibon Avel, St Mary the Virgin, Llanfair Kilgeddin, St Jerome, Llangwm Uchaf, St David, Llangeview, Dore Abbey, and Castle Chapel, Urishay.

On the 13–15 September: a weekend event based in Abergavenny St Mary’s will include a guided tour of all of the churches and a performance work by Holly Slingsby. Visit artandchristianity.org for more details.

The Friends of Friendless Churches was established by a group of friends in 1957 to save redundant but beautiful places of worship from demolition, decay, and unsympathetic conversion.

It believes that an ancient and beautiful church fulfils its primary function merely by existing. It is, in itself, and irrespective of the members using it, an act of worship.

A spokesperson for the group said, “These buildings are our greatest architectural and cultural legacy, shaping landscapes and lives for hundreds of years. They are the spiritual and artistic investment of generations, and they should survive for the benefit of future generations."

The Friends of Friendless Churches is an independent, non-denominational charity which receives no government funding in England, and a modest grant in Wales.

Art and Christianity seek to foster and explore the dialogue between art, Christianity, and other religious faiths. Through events, publications, and consultation, they offer education, enquiry, and exchange with regard to the relationship between art and faith.

Paula Gooder, Chair of Art and Christianity explained, “This rich and fascinating exhibition offers an opportunity for reflection not just on what a vessel is but on what a vessel might contain. Six stunning pieces of art in six beautiful church buildings will provide an art trail and pilgrimage against the backdrop of the Black Mountains. This is an experience not to be missed.”

Art and Christianity trustee Jacquiline added, “Curating contemporary art in these extraordinarily intimate churches, presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities. It requires careful consideration of the historical, spiritual, and architectural dimensions of each place. By selecting a narrative that resonates across the shared character of the churches and by placing a single work of art that represents a vessel within each of these exceptional ancient sites, we endeavour to create a spiritual environment that allows reflection, dialogue, and connection.”

Since 2009-2022 Jacquiline has been central to the development of visual arts programmes at Salisbury and Chichester among other Cathedrals. Now she is a freelance Visual Art Advisor and is engaged as the Consultant Curator for the Association of English Cathedrals. She is also a Trustee and Project Curator of A+C and Director and Curator for WAC.

Over the past 16 years, Jacquiline has delivered over 58 exhibitions, working with a diverse group of artists, galleries, foundations, and estates. These include Antony Gormley, Lemn Sissay, Mark Wallinger, David Mach, and Ana Maria Pacheco, galleries such as The Lisson, Osborne Samuel, Hauser&Wirth and the estates of Henry Moore, Lynn Chadwick, Barbara Hepworth and others.

She has developed lasting relationships with many of the leading figures in the contemporary art world whose dedication and support have been crucial to the success of the many projects delivered.

Turning her thoughts toward the current project and the artists involved, Jacquiline said, “The many definitions of the word ‘vessel’ emphasise the versatility and richness of the term, its potential interpretations providing a medium for creative expression, symbolism, and the exploration of concepts relating to containment, transportation, embodiment, and transformation.

“In Christianity, a vessel is often used as a symbol of the human body or soul, which is seen as a container for the Holy Spirit. The concept of the vessel is used to illustrate the idea that Christians are called to be vessels of God's love, grace, and power, and to carry the message of the Gospel to the world.

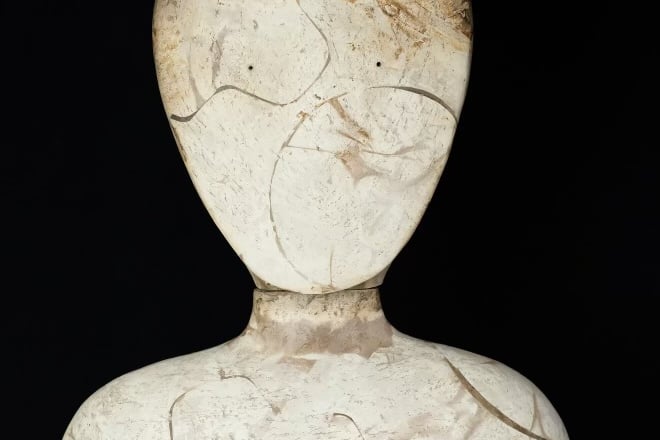

"Centre by Steinunn Thórarinsdóttir is an androgynous human form representing all of humanity. It is a solitary, graceful figure sited in the churchyard of St Mary, Llanfair Kilgeddin; its contemplative gaze is raised toward the bell tower. The figure is both classical and abstract, devoid of any definition, yet its human scale invites us to engage with it. Centre is created from rough cast iron, pierced with a glass circle creating a window to the soul, and the sculpture is placed so that light will shine through the glass at certain times of the day.

"Lucy Glendinning responds by using the human form as a vessel for emotions, ideas, and consciousness. She comes from a medical family and is researching Neuro-aesthetics, a scientific approach to the study of the aesthetic experience when considering a work of art. Lucy’s work incorporates pale feathers to remind us of our symbiotic relationship with the natural world and the context of a church draws us to contemplate angels and their wings. White Hart possesses an ethereal glow which can be glimpsed through the richly carved 15th-century rood screen, and pulls the visitor towards the side chapel of St Jerome Llangwm Uchaf in which it stands.”

Jacquiline added, "The use of different materials offers unique qualities and characteristics that have allowed the artists to express their ideas and emotions in new ways. Their choice of materials has enhanced the artists’ ability to communicate their intended message and create an engaging visual experience for the viewer.”

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.