ABERGAVENNY was once known as a railway town and many of its inhabitants were railwaymen.

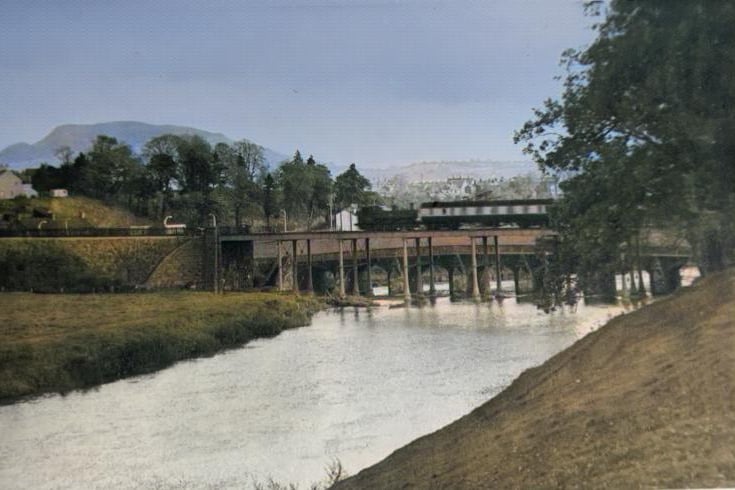

During its glory days, the great locomotive depot in Brecon Road and the town’s three busy stations defined the geography of the town.

All that remains now however are a few scattered remnants, buildings, and place names to help the inquisitive soul venture forth on the tracks of time and into a bygone era when the ‘iron horse’ was king and the hills were alive with the sound of steam.

Abergavenny still boasts a station that has survived the ravages of modernisation and still carries a quaint, old-fashioned atmosphere about it that one can imagine having a ‘Brief Encounter’ upon.

Yet despite all the rosy-eyed nostalgia which abounds in the modern world for the golden age of civilised travel and the aesthetic of the carriage, to many born into the era of the horse and cart, the locomotive was an infernal thing of great ugliness.

Take this letter printed in an Abergavenny Chronicle of 1908 for example.

“Dear sir, last Monday evening a few minutes to seven, we were walking to Llanfoist by the Castle Meadows. The hidden moon broke through a bank of cloud, and we turned to look at her, magnificent in her fullness, and in brilliancy dwarfing Jupiter, for to our ignorant eyes this planet appeared her close companion.

What was that before us? The creation of a moment; a lunar rainbow. The perfect bow stretched like an enchanted bridge of moonlight vapour. Behind it as a curtain of indigo dye, rose the Blorenge, its summit lost in heavy clouds - ‘a mountain over a mountain.’

Darkness clothed the valley of the Usk, but the whitewashed houses of Llanfoist Bridge reflected the light of the moon, and each window and chimney could be distinguished.

In silence, we gazed at that never-to-be-forgotten scene - a scene no pen could have painted or a French impressionist rendered.

Gradually it faded. The last of that rainbow ghost was carried away on the smoke of a passing train, one of the many things that mar the beauty of beautiful Abergavenny.”

Of course, fast-forward 40 years or so, and every kid in Britain wanted to work on the trains, as the now often ridiculed, but then, the hugely popular art of train-spotting clearly testified.

Take this Chronicle report from 1952 if you will.

"They poke their heads through station barrier rails, they perch on the parapets of railway bridges, they line the embankments; lie in wait at tunnels; stand patiently at level crossings; and gaze in wonder at the major junctions.

They are the trainspotters - that happy band of schoolboys who collect train numbers in much the same way as their mates collect stamps, matchboxes, and marbles. Abergavenny has quite a few of them.

As a hobby it has long gone unrecognised, but no longer, for now, the train spotters have their own mark of identity. It is a necktie which depicts a class of locomotive much loved by spotters.

The manufacturers of the tie have shown excellent psychology. Train-spotters may, with impunity, use their ties as pen-knife polishers or as hand de-greasers. For they are fully washable - yes indeed."

To this day nothing quite quickens the blood and enflames the passions of the rare breed of men who religiously refer to themselves as ‘train enthusiasts’ and never the more derogatory ‘trainspotter’, than the romance and nostalgia inherent in the form and force of a vintage steam train.

Whether you’re a train enthusiast or not, few people can remain unmoved by the sight of these rolling monuments to another age, pulling liveried coaches across open country. Think for a minute of the sublime splendor and rolling thunder of the Orient Express and the haunting lament that an old steam engine makes as it hurtles down the track, forever disappearing into and emerging from clouds of its own smoke.

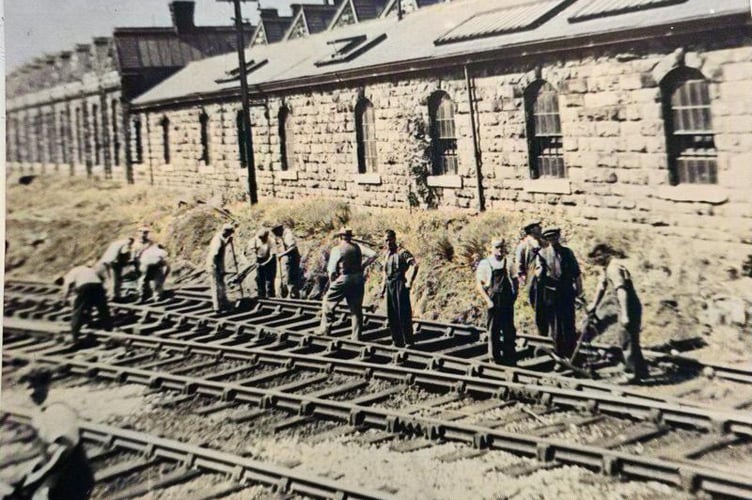

A former Abergavenny steam engine driver once told the Chronicle how on any given day he could walk through the town, where he grew up and worked in the first part of the twentieth century, and every other person he bumped into would be a railway worker of some description.

The man, who was then in his nineties, described how when he was a child every young boy wanted to grow up and become a steam engine driver and how the combination of steam, train, and tracks formed a secret brotherhood where men referred to one another as ‘Born railway-men with ‘Trains in their blood’.

He added, “Until you have hurtled down the tracks in the early hours of the morning going hell for leather in a ‘Great Western’ you haven’t lived.”